WASHINGTON ? It's become a symbol of sorts for the federal government's budget dysfunction: Unless Congress acts before Jan. 1, doctors will again face steep Medicare cuts that threaten to undermine health care for millions of seniors and disabled people.

This time it's a 27.4 percent cut. Last year, it was about 20 percent. The cuts are the consequence of a 1990s budget law that failed to control spending but was never repealed. Congress passes a temporary fix each time, only to grow the size of reductions required next time around. Last week's supercommittee breakdown leaves the so-called "doc fix" unresolved with time running out.

A thousand miles away in Harlan, Iowa, Dr. Don Klitgaard is trying to contain his frustration.

"I don't see how primary care doctors could take anywhere near like a 27-percent pay cut and continue to function," said Klitgaard, a family physician at a local medical center. "I assume there's going to be a temporary fix, because the health care system is going to implode without it."

Medicare patients account for about 45 percent of the visits to his clinic. Klitgaard said the irony is that he and his colleagues have been making improvements, keeping closer tabs on those with chronic illnesses in the hopes of avoiding needless hospitalizations. While that can save money for Medicare, it requires considerable upfront investment from the medical practice.

"The threat of a huge cut makes it very difficult to continue down this road," said Klitgaard, adding "it's almost comical" lawmakers would let the situation get so far out of hand.

There's nothing to laugh about, says a senior Washington lobbyist closely involved with the secretive supercommittee deliberations. The health care industry lobbyist, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to make public statements, said lawmakers of both parties wanted to deal with the cuts to doctors, but a fundamental partisan divide over tax increases blocked progress of any kind.

The main options now before Congress include a one-year or two-year fix.

The problem is the cost. Congress used to add it to the federal deficit, but lawmakers can't get away with that in these fiscally austere times. Instead, they must find about $22 billion in offsets for the one-year option, $35 billion for the two-year version. A permanent fix would cost about $300 billion over 10 years, making it much less likely.

"It's going to be a real challenge, and there's not a lot of time to play ping-pong," said the lobbyist. "It's entirely possible given past performance that Congress misses the deadline."

Congressional leaders of both parties have said that won't happen. Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus, D-Mont., says the Medicare fix is too important not to get done. But how? The endgame for a complex negotiation also involving expiring tax cuts, unemployment benefits and dozens of lesser issues remains unclear.

"They have to come up with a solution, and they will have to appear to pay for that solution, and that will be contentious," said economist Robert Reischauer, one of the public trustees who oversees Medicare and Social Security financing. One option: cut other parts of Medicare. Another: trim back spending under the health care overhaul law. Either of those approaches would mobilize opposition.

A nonpartisan panel advising lawmakers is recommending that doctors share the pain of a permanent fix with a 10-year freeze for primary care physicians and cuts followed by a freeze for specialists. Doctors aren't buying that.

The Obama administration says seniors and their doctors have nothing to fear.

But doctors are becoming increasingly irritated about dealing with Medicare. Surveys have shown that many physicians would consider not taking new Medicare patients if the cuts go through. Some primary care doctors are going into "concierge medicine," limiting their practice to patients able to pay a fee of about $1,500 a year, a trend that worries advocates for the elderly.

Ultimately, the solution is an overhaul of Medicare's payment system so that doctors are rewarded for providing quality, cost-effective care, said Mark McClellan, an economist and medical doctor who served as Medicare administrator for President George W. Bush. That continues to elude policymakers.

Instead, the threat of payment cuts has become a holiday tradition, said McClellan. "It's just not a very enjoyable one."

tim hightower waldorf school waldorf school new orleans saints world series game 4 world series game 4 indianapolis colts

Looking for a last-minute holiday gift? How about that Groupon you never used? Daily deal vouchers wouldn't actually make bad presents if there was a way to gift them that didn't involve an email printout tucked into a card. That's where

Looking for a last-minute holiday gift? How about that Groupon you never used? Daily deal vouchers wouldn't actually make bad presents if there was a way to gift them that didn't involve an email printout tucked into a card. That's where

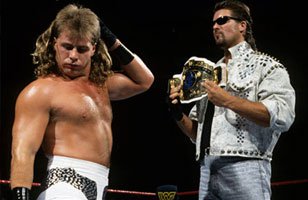

Seven months before Kevin Nash savagely attacked Triple H with a sledgehammer on WWE Raw SuperShow, the two men were standing with their longtime friends Shawn Michaels and Sean Waltman on the stage of Atlanta?s Philips Arena, celebrating HBK?s induction into the WWE Hall of Fame. It was a defining moment for the four Superstars who, along with Scott Hall, formed ?The Kliq? ? the most exclusive and, perhaps, most influential group in all of sports-entertainment.

Seven months before Kevin Nash savagely attacked Triple H with a sledgehammer on WWE Raw SuperShow, the two men were standing with their longtime friends Shawn Michaels and Sean Waltman on the stage of Atlanta?s Philips Arena, celebrating HBK?s induction into the WWE Hall of Fame. It was a defining moment for the four Superstars who, along with Scott Hall, formed ?The Kliq? ? the most exclusive and, perhaps, most influential group in all of sports-entertainment. Kliq. Formed by Michaels and Nash in the early ?90s, the ?Two Dudes with Attitudes? developed a tight bond both in and out of the ring. Soon, they became a trio with the addition of Razor Ramon (Scott Hall), Shawn?s old friend from his days in the AWA. Hall, in turn, introduced a young rookie named The 1-2-3 Kid (Sean Waltman) to the group.

Kliq. Formed by Michaels and Nash in the early ?90s, the ?Two Dudes with Attitudes? developed a tight bond both in and out of the ring. Soon, they became a trio with the addition of Razor Ramon (Scott Hall), Shawn?s old friend from his days in the AWA. Hall, in turn, introduced a young rookie named The 1-2-3 Kid (Sean Waltman) to the group. The power struggle was further complicated when a fifth member joined The Kliq in 1995. As the story goes, Triple H, upon arriving in WWE from WCW, walked right up to Shawn Michaels and told him he wanted to be a part of his crew. It was a bold move that immediately impressed HBK.

The power struggle was further complicated when a fifth member joined The Kliq in 1995. As the story goes, Triple H, upon arriving in WWE from WCW, walked right up to Shawn Michaels and told him he wanted to be a part of his crew. It was a bold move that immediately impressed HBK. split into two factions ? WCW?s New World Order and WWE?s D-Generation X. Both Nash and Triple H ascended to the top of their rival organizations while remaining close friends, but Big Kev faced failure when WCW crumbled around him in 2001. He moved in and out of the sports-entertainment realm after that, including a brief stop in WWE in 2002, but Nash seemed to flounder for much of the decade.

split into two factions ? WCW?s New World Order and WWE?s D-Generation X. Both Nash and Triple H ascended to the top of their rival organizations while remaining close friends, but Big Kev faced failure when WCW crumbled around him in 2001. He moved in and out of the sports-entertainment realm after that, including a brief stop in WWE in 2002, but Nash seemed to flounder for much of the decade. For Nash, that meant hitting his friend of 15 years with a sledgehammer so hard that it crushed the vertebrae in his neck. The assault put The King of Kings in the hospital, but both Michaels and Waltman can attest to the same fact ? Triple H always hits back.

For Nash, that meant hitting his friend of 15 years with a sledgehammer so hard that it crushed the vertebrae in his neck. The assault put The King of Kings in the hospital, but both Michaels and Waltman can attest to the same fact ? Triple H always hits back.